Categories

Why Another Development Organisation?

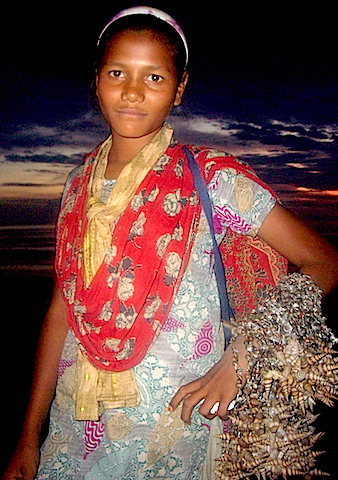

From memory, my first thought of establishing a new development organisation came to me on a beach in Bangladesh. Cox’s Bazar is said to be the world’s longest beach. It could also be the most crowded. It was November 2012 and I had just completed a very demanding six-month work assignment in South Sudan and was seeking some of the peace and tranquillity normally associated with a two week beach stay. But tranquillity wasn’t so easy to find. Each day I would try to escape the crowds and cameras by taking a long walk. If it really is the world’s longest beach, my emotionally fatigued mind felt in need of the world’s longest beach walk. Past the crowds and cameras and jet-skis and persistent micro-entrepreneurs, beyond the small fishing villages, until the only curious eyes were the cows resting on the beach. Then I would stop, take a long swim in the warm waters of the Bay of Bengal, and sit down with my books.

I had stumbled by accident into community development work and was very conscious of the fact I wasn’t qualified for the work I was doing. I met regularly with government ministers and negotiated projects with executive leaders from organisations such as UNFPA, MSF, IRC, USAID, WHO, WFP and UNICEF – all highly qualified and experienced leaders in their field. In contrast, I based my work on some simple principles I had learned along the way. I was determined to educate myself in at least the fundamentals of international development work.

One of the first books in my self-selected reading course was New Internationalist’s “No-Nonsense Guide to International Development” by Maggie Black. As I read, gradually I began to grasp the enormity of the global enterprise we call development – thousands of organisations, primarily from the world’s richest countries, spending billions of dollars, with a coordinated focus on eight development goals, one of which was to halve maternal mortality by 2015. It was an inspiring revelation – world leaders harnessing the vast resources of generous people from diverse languages and cultures to work in harmony to prevent mothers from dying in child-birth.

Except… I had just come from South Sudan where my major project for the year had been to establish a midwives training centre that had potential to halve the maternal mortality rate. At that time UNFPA, the world’s peak body for maternal health, estimated that South Sudan had the world’s highest rate of maternal mortality with up to one in seven women dying in childbirth. I couldn’t comprehend why, with all the resources of this enormous international movement, nothing seemed to be changing in this remote corner of the world. Just weeks earlier the Director of the Aweil State Hospital had told me they had recorded 200 maternal deaths that year – and he estimated the number was four times higher if we included those who didn’t come to the hospital for delivery.

My utopic vision was shattered as quickly as it had formed.

As I read more and more I began to see that the middle 5 billion of the world’s 7 billion people have made remarkable progress in economic development and standard of living over the past 40 years. However the bottom billion continue to be trapped in extreme poverty with no convincing evidence this is likely to change any time soon.

Other authors confirmed what I had seen in practice – wide spread program failure amongst the most disadvantaged of the world’s communities. The reasons are complex and numerous – cultural differences, communication barriers, lack of technology, inadequate training, neo-colonial practices, paternalistic attitudes, politically motivated agendas, corruption and mismanagement.

Sometimes, in the long term, program success can be even worse than failure. I have lived in regions where a high proportion of schools, clinics, bore holes, agricultural projects and programs for vulnerable children were proudly labelled with signs from the sponsors – nearly always an organisation from a country the local community could barely imagine. The psychological impact on the residents as they observe one sign after another is to conclude that not much is likely to change unless a foreigner comes to help. The disincentive is multiplied when local leaders who have toiled for years to mobilise their community to provide simple, effective programs see brand new facilities spring up as if by magic. Or when local hospitals and schools, struggling with their meagre resources to meet the needs of their community, suddenly lose their best staff to foreign organisations offering vastly higher salaries.

As I rested on the beach, read my books, and pondered my surprising success in complex work I barely understood, I began to explore what was needed for this work to continue. I had already decided I couldn’t continue with the organisation I was working with. Opportunities to assist communities facing extreme inequality were increasing by the day, but could I find an existing development organisation that would allow me to build on the values and core principles that were foundational to my work? I had my doubts.

The strongest indicator for project success that I had observed was the strength of friendship between the local community and the foreign donor. But which organisation includes “Friendship Analysis” in their project design?

With any project I have seen that has capacity for genuine social transformation, the initiative, leadership, management, ownership and responsibility have all come from within the community. But would any of the BINGOs (Big International Non-Government Organisations) detach from the pervasive “top down” models of project management?

Gradually it became obvious… we would need to start something new.

And so the dreaming began…

Comments (2)

Shila Phopo

reply

Mike

Thanks

reply